The presence of gaps in the dental arch, whether a single missing tooth or complete edentulism, initiates a profound psychological transformation that extends far beyond the tangible physical disruption. A smile constitutes a central, non-verbal component of human communication, a key element in self-presentation, and a significant contributor to the individual’s overall body schema—the inner, psychological image of the physical self. The loss of a tooth, therefore, is not merely a structural issue but an affront to one’s perceived identity and social currency, often leading to a complex spectrum of emotional and behavioral adaptations that compromise the quality of life in ways often underestimated by clinical assessments focused purely on masticatory function.

A smile constitutes a central, non-verbal component of human communication, a key element in self-presentation, and a significant contributor to the individual’s overall body schema.

For many individuals, especially when the missing teeth are visible, this physical alteration translates immediately into a diminished sense of self-worth. The smile, which ideally functions as a spontaneous gesture of friendliness and confidence, becomes instead a source of acute anxiety, transforming casual social interactions into deliberate exercises in concealment. Individuals often develop specific coping behaviors, such as suppressing laughter, minimizing the opening of the mouth while speaking, or strategically covering the mouth with a hand, all of which are designed to hide the perceived flaw. This constant, conscious self-monitoring drains cognitive resources and shifts the individual’s focus inward, away from the external world and the flow of conversation. Over time, this chronic self-consciousness begins to fundamentally restructure the individual’s social behavior, leading to a noticeable withdrawal from environments where open, unguarded interaction is expected.

This constant, conscious self-monitoring drains cognitive resources and shifts the individual’s focus inward, away from the external world and the flow of conversation.

The psychological distress associated with tooth loss frequently mirrors the established stages of grief, a response typically reserved for major life traumas or the passing of a loved one. The process often begins with an element of shock and denial, particularly if the loss was sudden due to an accident or trauma. This is rapidly followed by a phase of anger or frustration—anger directed at the circumstance, the self, or even the healthcare providers. As the permanence of the change sets in, a period of profound sadness or depression may follow, stemming from the feeling of having lost an essential, irreplaceable part of their body. Patients sometimes articulate this as a feeling of premature aging or a physical manifestation of a decline in their overall self-care. It is this emotional complexity that oral rehabilitation must address, recognizing that restoring function without acknowledging the preceding emotional toll is an incomplete therapeutic intervention.

The psychological distress associated with tooth loss frequently mirrors the established stages of grief, a response typically reserved for major life traumas or the passing of a loved one.

Social anxiety escalates dramatically in individuals grappling with edentulism or visible gaps. The fear is not just of being noticed, but of being negatively judged, an apprehension rooted in the societal stereotype that equates missing teeth with poverty, neglect, or lower educational attainment, regardless of the actual cause, which may be complex disease or genetic predisposition. This perceived social stigma can create a barrier to professional opportunities, as individuals may shy away from job interviews or public-facing roles that demand confident communication. The avoidance is cyclical; withdrawing from social situations prevents the individual from gaining positive reinforcement or challenging their negative self-perception, thereby solidifying the belief that their appearance is fundamentally unacceptable. The constant anticipation of scrutiny leads to a state of hyper-vigilance in any interactive setting.

This perceived social stigma can create a barrier to professional opportunities, as individuals may shy away from job interviews or public-facing roles that demand confident communication.

Beyond mere aesthetics, the loss of teeth can subtly interfere with the mechanics of speech. Anterior teeth are critical for the correct articulation of sibilant and fricative sounds, and their absence can lead to minor or sometimes pronounced lisping or whistling sounds during conversation. While this functional change may seem minor in isolation, when combined with the existing self-consciousness regarding appearance, the resultant communication difficulty acts as a multiplier for anxiety. The individual becomes less willing to initiate speech, often using fewer words or speaking in a lower volume to mask the articulatory challenges. This reduction in confident vocal participation limits their ability to fully express their personality or intellect in social and professional arenas, creating a genuine impediment to both personal and career growth.

The individual becomes less willing to initiate speech, often using fewer words or speaking in a lower volume to mask the articulatory challenges.

The long-term impact on body image is profound, as the mouth represents a focal point for identity. When this focal point is damaged, the psychological self-portrait can become distorted. Studies indicate that individuals with tooth loss, even when successfully rehabilitated with dentures, can retain a persistent level of body image dissatisfaction. This is particularly true for those with existing tendencies toward neuroticism or perfectionism, suggesting that the psychological fallout is filtered through pre-existing personality traits. The internal image of the self remains marred by the memory of the loss, a phantom discomfort that no amount of physical restoration can entirely erase without concurrent psychological support. This highlights the necessity of viewing tooth loss not as a singular event, but as a chronic assault on the integrity of the personal body schema.

This highlights the necessity of viewing tooth loss not as a singular event, but as a chronic assault on the integrity of the personal body schema.

A crucial, yet often overlooked, dimension is the interference with the enjoyment of food. The ability to chew efficiently and comfortably is essential for proper nutrition and is deeply interwoven with cultural and social bonding rituals. Missing teeth can severely limit dietary choices, leading to a shift toward softer, less fibrous foods, which may compromise nutritional intake over time. More immediately, the inability to comfortably participate in shared meals—a cornerstone of family life and social gatherings—can lead to further isolation. The individual may avoid eating in public entirely or become overly preoccupied with the mechanics of chewing, turning a moment of communal pleasure into a source of stress and embarrassment, reinforcing the cycle of withdrawal.

The individual may avoid eating in public entirely or become overly preoccupied with the mechanics of chewing, turning a moment of communal pleasure into a source of stress and embarrassment.

Coping mechanisms adopted by those dealing with tooth loss are varied and often maladaptive. They range from complete social avoidance and emotional withdrawal to compensatory behaviors, such as excessive preoccupation with other aspects of their appearance in an attempt to distract from the dental issue. A proactive, healthy coping strategy involves acknowledging the loss and seeking professional intervention, both dental and psychological. Talking openly about the feelings of embarrassment, anxiety, and sadness with a therapist or counselor specializing in body image or trauma can provide the necessary framework to process the emotional injury and develop adaptive strategies to manage social situations while awaiting or undergoing reconstructive treatment. This dual-pronged approach addresses both the physical reality and the psychological overlay.

A proactive, healthy coping strategy involves acknowledging the loss and seeking professional intervention, both dental and psychological.

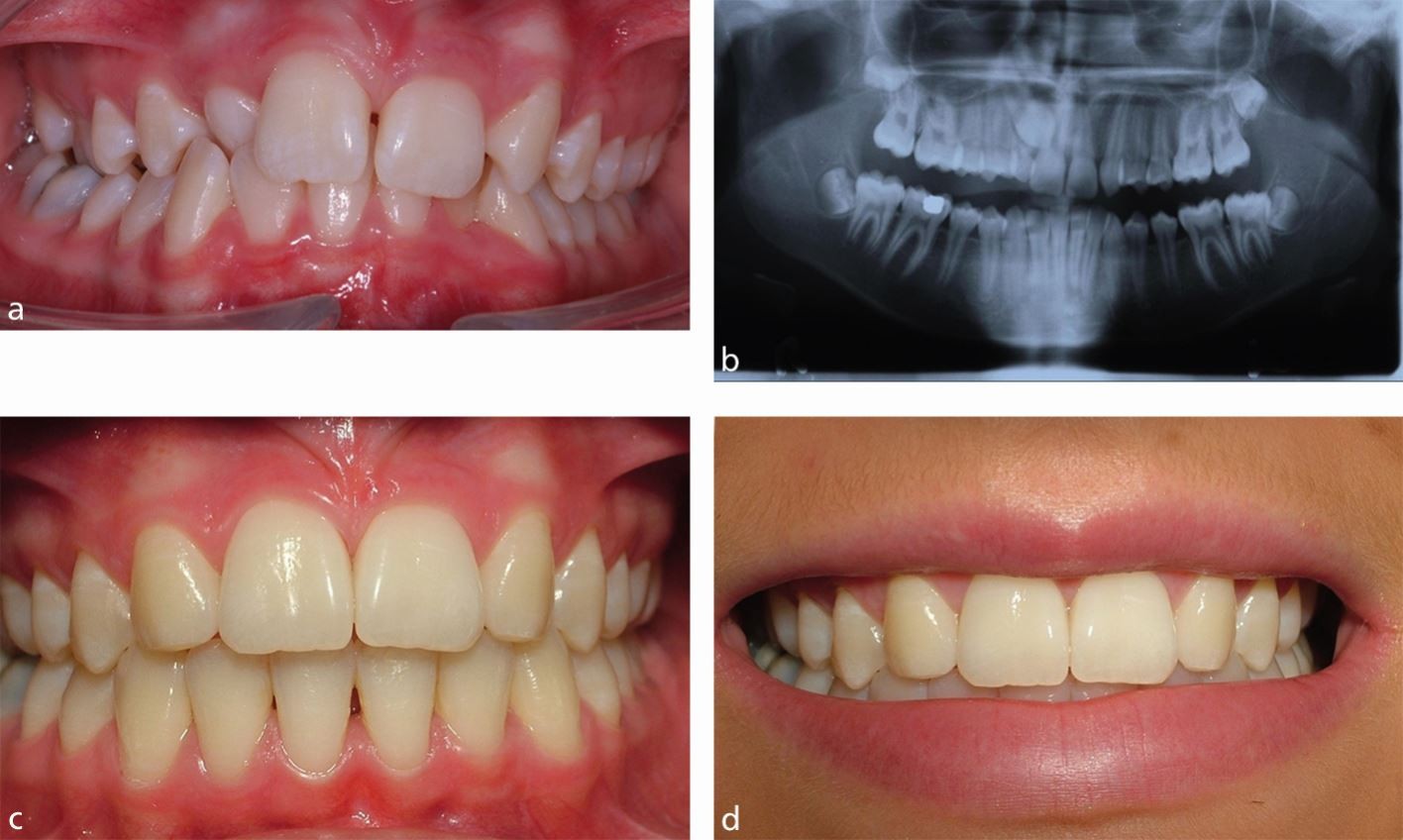

The decision to pursue restorative dentistry, such as implants, bridges, or dentures, is therefore as much a psychological investment as a physical one. Successful oral rehabilitation is frequently reported by patients not merely in terms of renewed chewing capacity, but more significantly, as a restoration of confidence and a reclaimed ability to smile freely and communicate openly without self-consciousness. The aesthetic outcome serves as a powerful psychological antidote to the earlier feelings of shame and unworthiness. It grants a tangible closure to the period of self-imposed isolation, allowing the individual to reintegrate fully into their social and professional life with a renewed sense of self-acceptance and composure.

The aesthetic outcome serves as a powerful psychological antidote to the earlier feelings of shame and unworthiness.

Ultimately, the psychological impact of missing teeth reveals the deep interconnectedness between physical appearance, social interaction, and mental well-being. It underscores the fact that the teeth are more than mere tools for mastication; they are anchors for personal identity and confidence. Effective management of tooth loss must, by necessity, adopt a holistic perspective that treats the psychological wound with the same urgency as the structural defect, thereby providing a pathway back to genuine self-acceptance and a truly unreserved smile.